Bailey

1. Research notes

1.1.Description of manuscript

Very thick firm paper. Sheet: 365 x 45 mm, folded across middle to form two leaves, stitched into sections with green cord.

Sections: 1) — 13 leaves; 2) – 20 leaves; 3) – 18 leaves; 4) – 20 leaves; and 5) – 13 leaves -> total 84 in all. Note that the sections do not correspond to the content.

1.2. Remarks

This manuscript seems to be the oldest textual witness of the zhal lce bcu drug. There is a date of composition (chu lug hor zla bcu pa) which seems to indicate the year 1583. However, neither the complete text has survived, nor does it appear to be a monolithic or 'single-cast' manuscript. The page numbers, probably added later, indicate that the first three folios (1a-3b) are missing, as the first page of the manuscript (hidden under the silk cover) is labelled page 4. Moreover, 14 pages previously left blank due to the original manuscript's binding have been written on in a different script (tshugs ma ‘khyug) (16a–16b3; 35b–36a; 53b–54a; 73b–74a; 84b–86b). Another hand also added the conversion table for compensation payments (81b–84a).

There are several indications that this manuscript must have been a student or research copy. While some manuscripts, such as Bell 16, show heavy signs of use and were produced in a handy travel size, Bailey — by its size alone (36,5cm x 4,5cm) — is too impractical for quick consultation.

There are also three glued bookmarks:

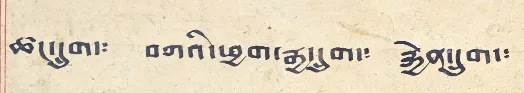

- [fol. 19b] reads zhal lce bcu drug, and marks the beginning of the actual pronouncements

- [fol. 29b] reads drug pa rku jag skor and marks the beginning of the sixth paragraph

- [fol. 46b], rkun khrims, marking the beginning of the twelfth paragraph.

Interpretation

The earmark དྲུག་པ་རྐུ་ཇག་སྐོར་ (theft/robbery) doesn’t match the actual chapter title, དྲུག་པ་ནག་ཅན་ཁྲག་ཅོར་གྱི་ཞལ་ལྕེ (heinous blood crimes). Since the manuscript’s first earmark correctly labels the whole text as ཞལ་ལྕེ་བཅུ་དྲུག, and chapter 12 is titled བཅུ་གཉིས་པ་རྐུས་པ་འཇལ་གྱི་ཞལ་ལྕེ (Adjudication of Theft), it is likely that these earmarks were added by someone for quick reference. The theft/robbery label suggests they saw robbery and violent crime as closely related, possibly because theft often involved force. This reflects a practical rather than strict textual reading, where legal cases of looting, banditry, or violent theft were handled under related statutes.

1.3. Palaeographical features

One noteworthy palaeographic feature is the use of an unusual punctuation mark which look like a colon or double tsheg(:), and serves primarily in two functions: tsheg replacement and final punctuation. The interesting aspect here is the shad marks - they seem to have a slightly decorative or elaborate form compared to the standard double shad we see in modern Unicode (།།).

Sam van Schaik notes that the double tsheg was a regular feature in Dunhuang legal texts but soon vanished towards the 10th century.

https://readingtibetan.wordpress.com/resources/punctuation/

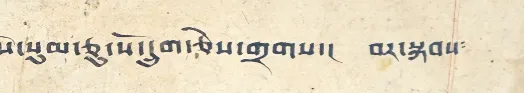

In this first example, we observe the final shad written almost as a colon.

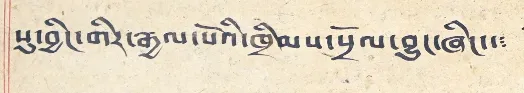

A second example shows its use as a tsheg at the end of a line.

This third example shows a triple colon after a final tsheg and shad.

This, however, is likely not a bsdus rtags (༴, U+0F34), meaning ‘etc’, or ‘ditto’, and used to mark repetitions.

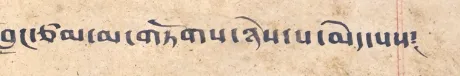

The mark here in this fourth example appears quite different - it looks almost like a decorative flourish with a more elongated vertical element.

- Does this specialized punctuation potentially serve specific functions in legal writing, similar to how modern legal texts often have their own conventions for organizing and demarcating text?

This variation in both form and function (alternating between shad-like and tsheg-like uses) makes it particularly challenging for Unicode representation. The fact that it can appear in these different forms – from the more dot-like structure to a more elongated version – suggests it might be more than just a simple punctuation variant.

- Could this perhaps be reflecting different scribal functions, like marking different types of breaks or transitions in the legal content? Or might it be serving some kind of emphasis function in certain contexts?

While these variations might be meaningful rather than just decorative, I will need to evaluate this during the translation process.

2. Table of contents

1. Invocation and praise [fol.4a1–7]

2. The Foundation of the Dharma and the Role of Royal Law [fol.4a7–5b3]

3. Historical Legal Precedents and the Current Ruler’s Authority [fol.5b3–6b5]

4. “Legal Survey”

4.1. Homicide: Compensation and Punishment (fol.6b5–9a3)

4.2. Wounding and Injury (fol.9a3–10a5)

4.3. Religious offenses, forgery, theft, and robbery (fol.10a5–11a6)

4.4. Adultery and Divorce (fol.11a6–11b7)

4.5. Oaths and Ordeals (fol.12a1–13b4)

4.6. Administrative regulations and Fees/Provisions (fol.13b4–15a5)

4.7. Concluding verses (fol.15a5–15b7)

The Bailey manuscript ends here. LTWA adds another 4 ½ folios, fol.16a7–18b4 including multiple glosses and marginal notes; consists of complex sets of calculations

Additional notes written in a different hand [16a–16b(2)]

While this text fragment is incomplete, it can be classified as མངོན་བརྗོད་, or descriptive writing. It offers vivid depictions of natural elements like clouds, rain, and lightning. The text also ties these elements to larger cosmic and symbolic ideas, showing how they fit into an interconnected system where nature reflects broader metaphysical truths. For example, clouds and rain are not just weather phenomena but are portrayed as part of a cycle that connects the earth and sky, symbolizing renewal and the flow of life. Similarly, light and shadow are depicted as forces that interact, representing balance and transformation in both the physical and spiritual realms—the natural world thus mirrors and participates in a cosmic order and these observations seemingly serve as a way of understanding existence through the lens of the elements.

5. Legal preface to the zhal lce bcu drug [fol.16b(3)–19b.5]

6.1. Invocation and Praise of Wisdom (fol.16b(3)–17a4)

6.2. Praise of the ruler and his lineage (fol.17a4–18a3)

6.3. Historical context (fol.18a3–19b5)

7. Zhal lce bcu drug [19b.6–52b.3]

- [19b.5–26a.4]

- [26a.5–27a.3]

- [27a.3–28a.6]

- [28a.6–29a.1]

- [29a.1–29b.2]

- [29b.2–30a.3]

- [30a.3–31b.2]

- [31b.2–35a.3]

- [35a.4–39a.5] Note: 35b–36a are additional notes in different hand

- [39a.6–41b.1]

- [41b.2–46b.2]

- [46b.2–46b.7]

- [46b.7–48a.5]

- [48a.6–49a.3]

- [49a.4–49b.3]

- [49b.4–52a.2]

7.17. Concluding verses (52a.2–52b.3)

8. Appendices

8.1. Furthermore, regarding various matters (fol.52b4–53a7)

8.2. Short regulation on the substitution of fines by compensation in kind [fol.53a7–54b3]

- fol.53b–54a contain additional notes and break the main text of the regulation; fol.54b contain more additional notes written in another hand]

8.3. Foundational policy document/Executive Order [fol.56a–58b]

8.4. A Decree of Güüshi Khan Justifying the Conquest of Tibet and Settling Affairs with the Karma Kagyü [fol.60a–65a]

8.5. Altan Khan’s (1507–1583) Legal Code [fol.66a–80b]

- Note: fol.73b–74a additional notes in different handwriting)

8.6. Conversion table for compensation payments

- [fol.81b–83b]